The St. Thomas School: Bach’s Leipzig Home

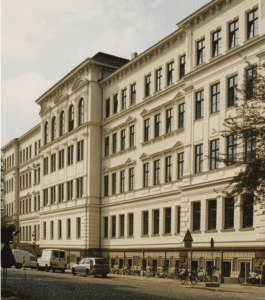

The St. Thomas School, Leipzig

Bach held many appointments in is lifetime for various cities and nobles throughout Protestant Germany, but none was more prestigious—or artistically productive—than his time at the St. Thomas School in Leipzig.

Not only did Bach hold this post from 1723 until his death in 1750, but he also had unprecedented access to skilled musicians trained under his own tutelage and an assortment of organs at various locations. In addition to dozens of cantatas, virtually all of his large-scale works were composed during his tenure. These include Passions for all four gospels (John and Matthew are extant, Luke disputed or partial), the Ascension Oratorio, Weihnachtsoratorium, and his immortal B Minor Mass.

These works would have almost certainly featured his students, faculty, and friends in leading roles, often with Bach at the keyboard. The world-renowned Thomanerchor—the boys’ choir at St. Thomas—was the inspiration for parts of the St. Matthew Passion, and the opportunities and influence of his time in Leipzig can be felt throughout the work from the final period of his life.

The Lead-Up to Leipzig

In the years prior to becoming the Thomaskantor, Bach wrote comparatively few cantatas and sacred works. His patron of six years—Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen—was an avid music lover, but his Calvinist inclinations called for austerity in worship.

As a result, this period was largely devoted to secular and instrumental music. In response, Bach composed some of his most refined compositions, including the six Brandenburg Concertos, the cello suites, Das wohltemperierte Klavier part 1, and the sonatas and partitas for solo violin.

Appointment at the St. Thomas School

The St. Thomas School was founded in 1212 by Augustinians, making it one of the oldest continually operated educational institutions in the world today. By Bach’s time, it was widely regarded as the best choral school in all of Protestant Germany, and the appointment placed him in charge of the music for four area churches, oversight of the school’s musical curriculum, and access to the city’s finest musicians.

A Passion for Passions

In his first year at St. Thomas, Bach began a project writing a Passion for each of the four Gospels that would consume most of the remaining years of his life either in composition or revision. Work commenced on the St. John Passion almost immediately following his appointment.

The result was a sweeping, dramatic personal expression of his faith and art that solidified the new Thomaskantor’s reputation. Despite a last-minute move of the premiere from St. Thomas to St. Nicholas, the work was immediately received as a powerful, emotionally rich expression featuring both compelling counterpoint and inspired structure.

Bach followed up this success with a work that is synonymous with grand scope and scale. The St. Matthew Passion is by far his largest and most daring composition, scored for two complete orchestras, choirs drawn from St. Thomas Church, and the Thomanerchor.

The inspiration for the double choir was likely the two lofts on either side of the nave, and despite reconstructions, you can still find this feature in the church today.

A Profusion of Cantatas

Possibly because of his limitations in the court of Prince Leopold, Bach began composing a cantata a week for the next six years of his life. This furious pace produced some of his most intricate and expressive small-scale works. This period included timeless favorites such as Wachet auf (BWV 140) and Herz und Mund (BWV 147) in addition to highly creative, innovative works like Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen (BWV 49)

By the time he exhausted himself, Bach had created five complete cycles of the Lutheran liturgy—over 300 cantatas in total—of which approximately 200 still survive today.

The Later Years

The remainder of Bach’s time in Leipzig (1729-1750) is roughly divided into his Middle and Late periods. His St. Mark Passion (1731) was completed during this time, although the manuscript was lost shortly after his death. The libretto by Picander still exists, and various reconstructions have attempted to revive Bach’s work.

St. Thomas Church, Leipzig

Bach also completed the Weihnachtsoratorium during 1734, and this marks the beginning of a period of reflection, summary, and evolution in his final years. He published his first set of organ works in 1739 and devoted a second set of preludes and fugues in every key in celebration of advancements in keyboard temperament.

His ideas about counterpoint also evolved during this time, and he created works such as the Art of the Fugue as both artistic and pedagogical artifacts for future generations of composers. He also spent many hours revising his Passions and putting the final touches on his artistic legacy.

The Last Triumph

In this vein, the final major work of Bach’s long life was the assembly of the towering B Minor Mass.

Why Bach chose to write it in Latin—the language of the traditional mass—is unknown. But the incredible artistic scope, emotional breadth, and compositional perfection are undeniable in any language, creed, or context. The work is about 2 hours long and features some of the finest contrapuntal writing Bach ever created.

The B Minor Mass also serves as a final commentary on Bach’s aretistic perspective. Despite being nearly blind at the end of his life, losing 10 of his 20 children, and suffering the death of his first wife, the B Minor Mass exemplifies an artistic ideal that elevates hope over despair, and promise over pain.

The final chorale, Dona nobis pacem (Grant us peace), is a restatement of the Gratias agimus tibi (We give thanks to Thee). This musical metaphor is both an invocation and a declaration of the musical legacy of Bach’s music; despite the suffering, pain, and tragedy we all endure, his final message to us is one of hope, optimism, and a belief in the good and beautiful to which we can all aspire.

Bach’s Enduring Legacy at St. Thomas

Bach died in 1750 shortly after finishing the B Minor Mass, and it was never performed in its entirety in his lifetime. When he passed, he was buried in an unmarked grave in St. John’s Church outside of Leipzig.

Like his music, he was quickly forgotten by history for nearly a century until the St. Matthew Passion was rediscovered by Felix Mendelssohn. This renewed interest in the Baroque master led to the rediscovery of his earthly remains in the late the 19th century.

Bach’s final resting place is in St. Thomas Church, just down the road from the St. Thomas School. The Thomanerchor he directed is still considered one of the more prestigious boys’ choirs in the world. Today, his bronze monument oversees the St. Thomas Church grounds, a museum bearing his name, and looks fondly in the direction of the St. Thomas School where he spent so many years of his life.